How to Kill Your Startup Before It Starts

author: Michael Thomas Mahoney

Whether you’re a research scientist in a lab or a startup in a garage… you’re isolated… you’re stuck in one place… you’re stuck in your own mindset and you’re believing every assumption you make about the problem and your solution to be the absolute, unequivocal truth. And this makes it really difficult to understand the problem, and the diverse group of stakeholders, and the customer that you’re trying to create a solution for. Mike Mahoney will show you what to do to avoid this kind of a failure…

I was recently asked to give a presentation during Clipster’s 4th Mixer Final to kill time while the judges deliberated over who would take home the PLN 20,000 prize. I reluctantly agreed, part in an attempt to prove myself as the newest member of the Clipster team and part in attempt help alleviate the stress that had been building around the office in the days leading up to the event.

When I asked what I should talk about, my project manager, Darek, said, “I don’t know…something startup related.”

“Okay,” I thought, “This won’t be so bad.”

Then I asked the question I should have asked before agreeing to the presentation in the first place, “How long does it need to be?”

“I don’t know…” Darek said, “Probably around 20 minutes.”

“Fuck,” I thought.

See, I hate public speaking. My mouth dries up. My voice waivers and cracks. I mumble. I ramble. I stand too still. I move too much. I talk too fast. Time slows down. I get faint. I get sweaty. I’m a monotoned mess.

“What the fuck am I going to talk about for 20 minutes?” I thought.

And then it hit me like a bullet, ‘The Importance of Experimental Design in Validating Business Assumptions.’

I jotted down a few notes, while the inspiration was still with me, and then I forgot about it until the day of the event.

Even still, I must not have done that terrible because Jarosław Łojewski contacted me and asked if I wouldn’t mind writing an article about my experience.

How to kill your startup before it starts?

I used to work in biotech, as a research scientist, doing validation studies for pharmaceutical clients, amongst other things. I’ve seen so many examples of bad data and poorly designed experiments over the years:

- Correlation and causation.

- Pointing to outliers as definitive proof.

- Testing too many variables at once.

- Blatantly obvious confirmation bias.

And this is among scientists!

When you’re not objective… when you’re not looking for the actual truth… whatever that might mean… then you’re going to end up with misleading data. And acting on that data can be very dangerous.

For examples of this, I recommend reading, „Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy” by Cathy O’Neill.

Business is harder than science

When it comes to testing business assumptions this can be even trickier. Because in the business world we’re no longer dealing with objective science, we’re dealing with human beings. And human beings are unique, and irrational, and unpredictable, and can have different motivations that lead them to seek out the same solution.

Setting up a valid, testable hypothesis is hard to get right, but very important. The purpose of designing and testing business hypotheses isn’t to prove yourself right and prove that you have an awesome idea. A well-designed business experiment will provide you with valuable information regardless of the outcome.

Whether you’re right or wrong, you will learn something about your customer, or the market, that you can then use to refine and iterate and test again.

With a well-designed experiment, all data is good data. With a poorly designed experiment, data can be the poison that wastes your startup’s time and effort and resources.

That’s why it’s so important to learn how to become an impartial observer. By questioning every assumption, you can avoid confirmation bias and discover deeply meaningful and actionable insights.

The problem is, whether you’re a research scientist in a lab or a startup in a garage… you’re isolated… you’re stuck in one place… you’re stuck in your own mindset and you’re believing every assumption you make about the problem and your solution to be the absolute, unequivocal truth.

And this makes it really difficult to understand the problem, and the diverse group of stakeholders, and the customer that you’re trying to create a solution for.

Because the problems don’t exist in the lab or the garage; the problems exist outside the building, in the real world. And in order to truly understand your customer and their problem, you have to understand their motivations, their needs, and how they currently meet their needs or how they work around them.

In order to identify real opportunity, where you can create real value for your customers, you need to…

GET OUT OF THE BUILDING!

#SteveBlank

You need to go out and actually talk to potential customers and others affected by the problem you’re trying to solve.

Because you’ll quickly find that you don’t understand the problem very well at all, and there’s a lot more involved than you initially thought.

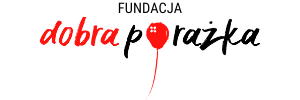

For example, I used to work with pharmaceutical companies, and when you’re developing a new drug, your end-user is the patient taking the drug, but the purchaser of your product, your actual customer is completely different, it’s the pharmaceutical wholesalers… and they sell to the pharmacies, who then sell to the patient’s. But there’s also doctors involved and pharmaceutical reps, and regulators… and always leering like a black cloud over your head, is the competition.

Author: Mike Mahoney

There are so many other stakeholders that you have to consider that might affect your product.

Quantitative Data

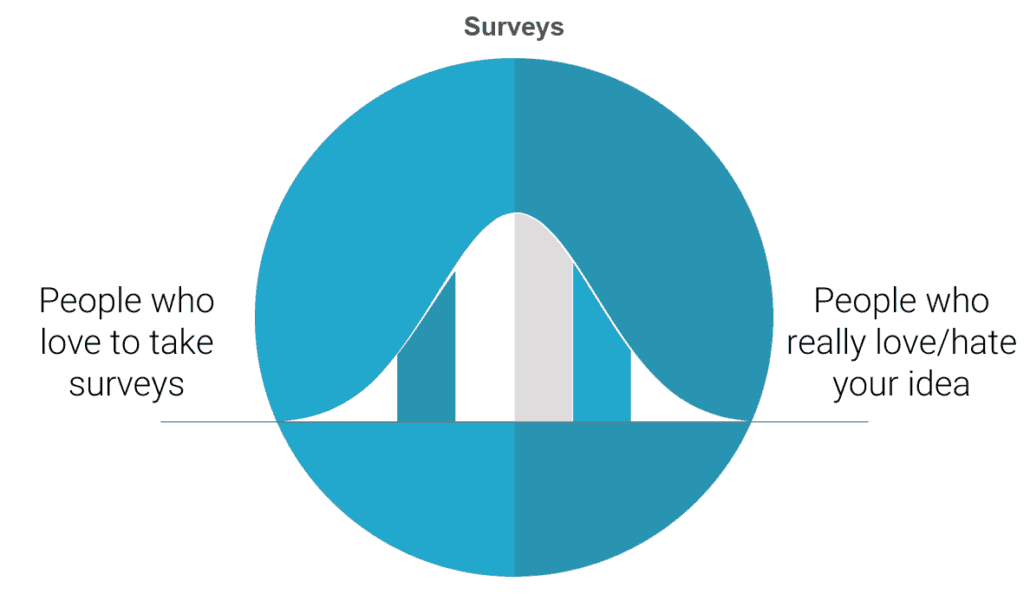

Surveys can tell you a lot, they’re good at gathering demographic information, and they’re quick and cheap, and you can easily gather data from a large number of people.

But they will rarely tell you something deeply insightful.

In fact, the one thing you can be sure that a survey will always tell you is that:

People fucking hate taking surveys.

Author: Mike Mahoney

You’ll usually only get responses from those on the extreme ends of the spectrum, and it’s hard to get representative data, and it can quite often be misleading.

In some cases, identifying the extreme users that either love or hate your product can be very helpful, but when startups use results like “90% of respondents loved our idea” as validation, they’re basing their decision to move forward on the extreme ends of the bell curve that may not represent a justifiably large enough market size.

Another problem with surveys is that the data is self-reported… and people lie!

I know I do.

If an anonymous survey on Facebook asks me how many times I worked out last week, I’m most likely going to protect my ego and fudge the numbers and pad my stats. It’s irrational, that I feel the need to lie to a computer that’s anonymously compiling my answers with millions of others, in order to make myself feel better, but we all do it.

But, if someone asks me to my face, or right after I climb a flight of stairs, I’ll probably keep the real number closer to the truth.

Additionally, survey questions are often irrelevant, poorly designed (leading questions), and the surveys themselves are often too long (so users start making shit up just to complete them) and sent to the wrong target audience.

Qualitative Data

That’s why I recommend that startups put more of a focus on qualitative data.

When I took part in the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps program, they taught us, religiously, the art and value of gathering qualitative data through the customer discovery interview process. And I’m going to share with you some of my tips and best practices. But first, l want to provide a famous business case, and also, one from my own experience that demonstrates the power of customer discovery interviews to reveal real opportunity and avoid chasing bad or biased data.

A story about construction workers

In 1992, DeWalt released its first line of portable electric power tools that all ran off the same standard, rechargeable Li-ion battery. This was revolutionary for residential contractors and construction workers, and it completely disrupted the market. But soon afterward, competitors began to saturate the market with similar products, so that by the late 90’s DeWalt needed a drastic new innovation to recover its once dominant market share.

So, they hired an intern, with no particular experience in the construction or power tool industry, and they flew her around to job sites all over America and told to her observe and document the most common things she saw being used on construction sites.

After months of this, they brought her back in to present her findings to DeWalt’s top executives. What she reported back was not what they were expecting. The top 3 things that she observed being used on job sites were pencils, lunch boxes, and radios. The executives were furious… this wasn’t the results they were looking for, this didn’t confirm that assumptions about which set of power tools to innovate on next, but this was the story the data told.

See the intern, being inexperienced, was a mostly impartial observer. And since she was never given instructions to look for what tools were used most on construction sites, she gathered her data in the most literal sense, looking for the items that people actually interacted with the most on job sites.

There is a true opportunity, probably…

But DeWalt then took this objective, impartial data, and went back to follow up on it. And after talking to multiple construction workers, they were beginning to find a trend. And here’s where they appropriately used quantitative surveys to scale and follow up with a larger set of construction workers quickly to start to reveal a real an opportunity. They discovered the construction workers would go through an average of 3 radios a year because they would get damaged on the job site. Additionally, workers reported they didn’t like having to sacrifice one of the limited plugs on construction sites to plug in their radios, but that they couldn’t work without music.

These were the true, deep insights that DeWalt needed to find out in order to innovate. With this information, they were able to design a durable radio built specifically for construction workers that ran off the same rechargeable Li-ion battery use by the rest of their toolset. The DeWalt Worksite Radio launched in 1999 and sold 1.5 million units in its first year, making it the best product launch in DeWalt’s history, far surpassing industry standard launches of the time by more than a factor of 10.

But they were only able to discover this opportunity by collecting objective data and following up by talking with actual customers.

Personal Experience

Now my own story isn’t as impressive, but it still demonstrates the value of conducting customer discovery interviews, and more importantly, it relates to startups as opposed to giant, established corporations with large R&D budgets.

So, some years back, I was working with a professor of pharmacology who had received a grant to develop new technology for studying complex biochemical networks. He had it in his mind that the best way to do this was with Virtual Reality, and so he went out and bought an Oculus Rift headset and a state-of-the-art computer with his grant money, all before even validating the concept. He loved his idea, to him it was his baby, so despite no interest from the scientific community, he continued to try and develop the concept his way.

I was brought on as a graduate research assistant to help bring his vision to life. But instead, I approached it as a skeptic and insisted on conducting customer discovery interviews with relevant stakeholders to gather some insight and understand the problem and the group he was targeting.

What I discovered was that the specific problem he wanted to solve wasn’t really a problem for anybody else. And, in the rare case where they did share this problem, they had other, faster, easier ways of working around it. So, the problem he was trying to solve wasn’t big enough, and the market he was targeting wasn’t really there.

The second thing I discovered, and this was purely through observation (which is why in-person interviews are always preferred) was that most researchers in this field wore corrective lenses, and you can’t comfortably wear a VR headset with glasses on. So, these researchers would never have adopted this solution anyway, purely based on ergonomics. So, after 30, high-quality interviews, I had enough data to convince him that he was going about this wrong and that he needed to pivot…and he did.

The pivot

I was able to convince him to use the remainder of his grant money to hire on a computer science graduate student and buy an Augmented Reality headset (Microsoft Hololens), to develop something that actually fulfilled a market need.

What he built was an Augmented Reality program to compile MRI scans to create custom 3D models of patients for surgeons to study and prepare, prior to surgery. This method was faster than the current methods of 3D-printed models by a factor of 10 and allowed for color-coding, and better manipulation of the model, such as the ability to zoom or focus in on one particular problem area. He has since spun-off this research into a successful Startup called Immersive Data Analytics and already has 3 hospital systems as clients.

source: [2]

I hope that the above stories have convinced you not to get too involved with early, un-vetted implementation of your beloved idea by wasting valuable resources. It is worth it to check if it makes sense first by getting out of the building.

In the next post, I will present the Customer Discovery Interview method and the principles of its proper use, allowing you to obtain valuable information about your product, stakeholders, customers, and users. Stay tuned!

About the Author: Michael Thomas Mahoney is an American graduate student, from Virginia Commonwealth University, completing his master’s research in Product Innovation by working abroad in Gdansk, Poland as the International Partnerships Specialist for Clipster, Poland’s first and only co-living/co-working accelerator program for digital nomads.

Heading picture source: [2]

[1] https://news.vcu.edu/article/Augmented_reality_revolutionizes_surgery_and_data_visualization